#Ancestral Puebloan People

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

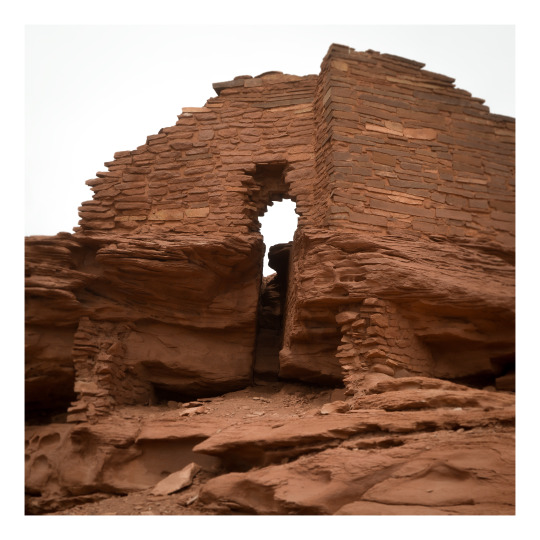

The Wukoki ruins at Wupatki National Monument, in Coconino County, Arizona.

#photographers on tumblr#landscape#ruins#Wukoki#Wupatki National Monument#San Francisco Peaks#Ancestral Puebloan People#Coconino County#Arizona

241 notes

·

View notes

Video

Sunset House Cliff Dwelling from Sun Point Overlook (Mesa Verde National Park) by Mark Stevens Via Flickr: A setting looking to the east while taking in views across Fewkes Canyon to the cliff dwellings of the Sunset House present in this part of Mesa Verde National Park. This was while on the 700 Years Tour with an overlook view from the Sun Point View.

#700 Years Tour#Ancestral Puebloan#Ancestral Puebloan Archaeological Sites#Archaeological Preserve#Archaeological Sites#Azimuth 88#Cliff#Cliff Dwellings#Cliff Walls#Colorado Plateau#Day 6#DxO PhotoLab 7 Edited#Evergreen Trees#Evergreens#Fewkes Canyon#Intermountain West#Landscape#Landscape - Scenery#Looking East#Massive Cliff Dwellings#Mesa Verde National Park#Nature#New Mexico and Mesa Verde National Park#Nikon D850#No People#Outside#Partly Sunny#Project365#Pueblo Buildings#Rocky Mountains

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, would you be willing to elaborate on that "disappearance of the Anasazi is bs" thing? I've heard something like that before but don't know much about it and would be interested to learn more. Or just like point me to a paper or yt video or something if you don't want to explain right now? Thanks!

I’m traveling to an archaeology conference right now, so this sounds like a great way to spend my airport time! @aurpiment you were wondering too—

“Anasazi” is an archaeological name given to the ancestral Puebloan cultural group in the US Southwest. It’s a Diné (Navajo) term and Modern Pueblos don’t like it and find it othering, so current archaeological best practices is to call this cultural group Ancestral Puebloans. (This is politically complicated because the Diné and Apache nations and groups still prefer “Anasazi” because through cultural interaction, mixing, and migration they also have ancestry among those people and they object to their ancestry being linguistically excluded… demonyms! Politically fraught always!)

However. The difficulties of explaining how descendant communities want to call this group kind of immediately shows: there are descendant communities. The “Anasazi” are Ancestral Purbloans. They are the ancestors of the modern Pueblos.

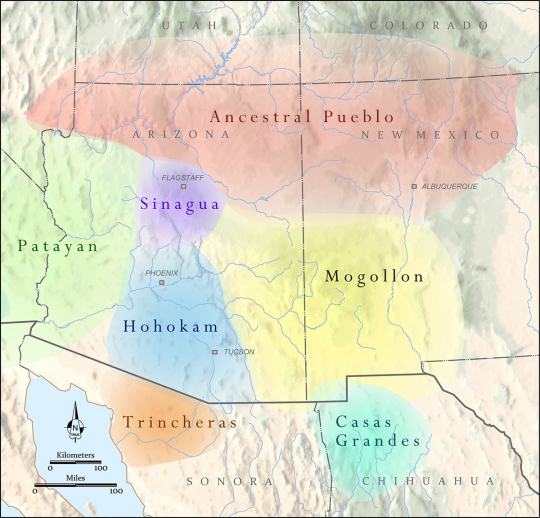

The Ancestral Puebloans as a distinct cultural group defined by similar material culture aspects arose 1200-500 BCE, depending on what you consider core cultural traits, and we generally stop talking about “Ancestral Puebloan” around 1450 CE. These were a group of people who lived in northern Arizona and New Mexico, and southern Colorado and Utah—the “Four Corners” region. There were of course different Ancestral Pueblo groups, political organizations, and cultures over the centuries—Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Kayenta, Tusayan, Ancestral Hopi—but they generally share some traits like religious sodality worship in subterranean circular kivas, residence in square adobe roomblocks around central plazas, maize farming practices, and styles of coil-and-scrape constructed black-on-white and black-on-red pottery.

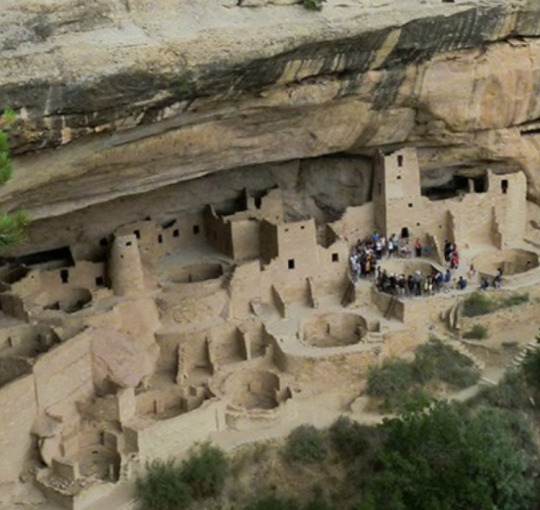

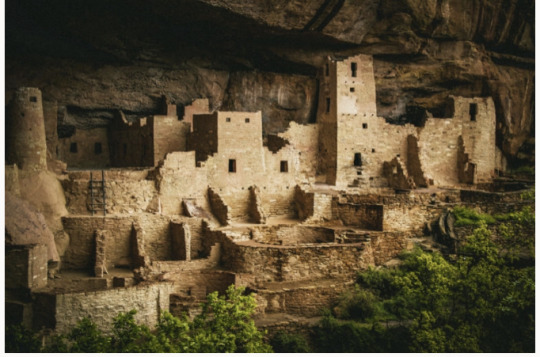

The most famous Ancestral Pueblo/“Anasazi” sites are the Cliff Palace and associated cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado:

When Europeans/Euro-Americans first found these majestic places, people had not been living in them for centuries. It was a big mystery to them—where did the people who built these cliff cities go? SURELY they were too complex and dramatic to have been built by the Native people who currently lived along the Rio Grande and cited these places as the homes of their ancestors!

So. Like so much else in American history: this mystery is like, 75% racism.

But WHY did the people of Mesa Verde all suddenly leave en masse in the late 1200s, depopulating the whole Mesa Verde region and moving south? That was a mystery. But now—between tree-ring climatological studies, extensive archaeology in this region, and actually listening to Pueblo people’s historical narratives—a lot of it is pretty well-understood. Anything archaeological is inherently, somewhat mysterious, because we have to make our best interpretations of often-scant remaining data, but it’s not some Big Mystery. There was a drought, and people moved south to settle along rivers.

There’s more to it than that—the 21-year drought from 1275-1296 went on unusually long, but it also came at a time when the attempted re-establishment of Chaco cultural organization at the confusingly-and-also-racist-assuption-ly-named Aztec Ruin in northern New Mexico was on the decline anyway, and the political situation of Mesa Verde caused instability and conflict with the extra drought pressures, and archaeologists still strenuously debate whether Athabaskans (ancestors of the Navajo and Apache) moved into the Four Corners region in this time or later, and whether that caused any push-out pressures…

But when I tell people I study Southwest archaeology, I still often hear, “Oh, isn’t it still a big mystery, what happened to the Anasazi? Didn’t they disappear?”

And the answer is. They didn’t disappear. Their descendants simply now live at Hopi, Zuni, Taos, Picuris, Acoma, Cochiti, Isleta, Jemez, Laguna, Nambé, Ohkay Owingeh, Pojoaque, Sandia, San Felipe, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Tamaya/Santa Ana, Kewa/Santo Domingo, Tesuque, Zia, and Ysleta del Sur. And/or married into Navajo and Apache groups. The Anasazi/Ancestral Puebloans didn’t disappear any more than you can say the Ancient Romans disappeared because the Coliseum is a ruin that’s not used anymore. And honestly, for the majority of archaeological mysteries about “disappearance,” this is the answer—the socio-political organization changed to something less obvious in the archaeological record, but the people didn’t disappear, they’re still there.

448 notes

·

View notes

Text

A crash course in some vocabulary

Archaeology, like all sciences, has a lot of specialized jargon we use to talk about pottery. To make sure everyone’s on the same page, here’s a list of some common terms I’ll be using, what they mean, and how to pronounce them.

~ 🏺🏺🏺 ~

Ware: A broader term for a technological/cultural tradition in pottery. Typically, construction method, color, clay type, temper type, and paint type are what defines a “ware.” So Chuska Gray Ware is unslipped, usually unpainted gray clay with crushed black basalt temper. Roosevelt Red Ware is red-slipped clay with sand temper and carbon-based paint. Hohokam Buff Ware is unslipped or cream-slipped buff-colored clay with coarse sand temper, created using a paddle-and-anvil forming method and painted with red paint.

Type: Within a ware, a type is a more narrowly specific decorative style. Roosevelt Red Ware has multiple types within it, such as Salado Red (unpainted red-slipped), Pinto Black-on-red (black paint on the red in a specific radially symmetric interlocked hatched-and-bold pattern), Pinto Polychrome (same decorative style but on a white-slipped interior field), Gila Polychrome (red exterior, white-slipped interior, a usually-broken black band around the rim, black painted designs in a two- or -four-fold symmetry), Tonto Polychrome (bolder and less symmetric black-and-white designs on a red field), Cliff Polychrome, Dinwiddie Polychrome, Nine Mile Polychrome… different stylistic variations on the Roosevelt Red Ware technological/visual core. You can read more about categorizations here.

A note on naming conventions: Pottery in this archaeological tradition tends to have a two-part name: a location where it was first defined and described, and a colorway. Wares tend to be “[Broad location or broad cultural group] [Color] Ware”; types tend to be “[Specific site] [paint color]-on-[clay color].” So within Tusayan White Ware is Flagstaff Black-on-white.

———

Gila: A river in southern Arizona and a bit of New Mexico, and a lizard and a polychrome type named after it. Pronounced hee-la.

Hohokam: An archaeological term for a Native American cultural group that lived in southern Arizona and northern Sonora, defined by traits like red-on-buff pottery, massive canal systems for field irrigation, and platform mounds. It comes from the O'odham-language word huhugham, “ancestors.” They are the ancestors of the modern Tohono O’odham and Akimel O’odham people (it’s a little bit more complicated than that but that’s basically the case.)

Mogollon: An archaeological term for a Native American cultural group from central New Mexico, eastern Arizona, and northern Chihuahua. Most iconic trait is the elaborate range of corrugated and smudged pottery. Named after the Mogollon Rim, the geological formation that marks the edge of the Colorado Plateau and a drastic change in geology and climate in the northern Southwest and the southern Southwest. Along with the Ancestral Pueblo, the Mogollon culture are ancestors of modern southern Rio Grande and Zuni pueblos. Pronounced moh-guh-yon.

Olla: A water jar with a wide body and narrow neck. Pronounced oy-ya.

Polychrome: Pottery that is three or more colors (poly+chrome), most often meaning red, white, and black.

A Tonto Polychrome olla. Southeastern Arizona, 1350-1450.

Pueblo: A collective term for Native people of the Southwest US (particularly in the Rio Grande river watershed, but also Hopi and Zuni) who share cultural traits and history—most immediately notably, a tradition of living in square adobe houses in large villages, which are also each called pueblos. Ancestral Pueblo is the term for the archaeologically-defined cultural group that share these similar traits and are, generally, from the northern half of New Mexico and Arizona, and a southern strip of Colorado and Utah. The Ancestral Puebloans were formerly called “Anasazi” but that has fallen out of favor due to pushback from modern Pueblos. Also, each modern Pueblo prefers to be called a Pueblo rather than a tribe in most cases—so you say the Pueblo of Acoma, the Pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh, Picuris Pueblo, Taos Pueblo, the Pueblo of Zuni, etc.

Temper: Non-clay bits that are added to natural clays to make them easier to work with. When you buy clay from a store now, it’s already mixed and processed and ready to use. When you find clay out in nature, it’s almost never so easy. Typically, you have to mine/harvest clay from riverbanks or cliffsides, and it’s hard and dried; then you have to grind the hard clay up into fine particles, and mix them with water. But natural clays are often puddly and don’t always hold together well, so you add temper, something hard and grainy to make your wet clay stick together more easily and make it good to work with! Temper can be sand, ground-up rock, ground-up shell, or even ground-up bits of other broken pottery. What different people used as temper is one defining feature of a pottery ware and pottery tradition.

Sherd: A broken bit of pottery. NOT shard. When it’s pottery, it’s “sherd.”

Slip: Very runny wet clay. It’s used to help attach clay pieces together, but more pertinently here, plain-colored pots are covered with an even layer of bolder-colored clay slip to get the desired color pot.

Smudging: A decorative style that potters made during the firing stage. They would have open pit-fires for firing their pottery, and cover the desired part of the pot with a layer of charcoal or ash. This creates a carbonized, reducing environment—that is, a lot of carbon, and little oxygen. This creates a smooth, inky black finish on the completed pot.

A Starkweather Smudged bowl. Mogollon, western New Mexico, AD 900-1200.

Vessel: Another word for pot, basically. Means a ceramic container of some sort. Bowls, jars, ladles, pitchers, mugs, etc are all vessels; effigies and statuettes are not.

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chaco Canyon

Chaco Canyon was the center of a pre-Columbian civilization flourishing in the San Juan Basin of the American Southwest from the 9th to the 12th century CE. Chacoan civilization represents a singular period in the history of an ancient people now referred to as "Ancestral Puebloans" given their relation to modern indigenous peoples of the Southwest whose lives are organized around Pueblos, or apartment-style communal dwellings.

Chacoans built epic works of public architecture which were without precedent in the prehistoric North American world and which remained unparalleled in size and complexity until historic times - a feat which required long-term planning and significant social organization. Precise alignment of these buildings with the cardinal directions and with the cyclical positions of the sun and moon, along with an abundance of exotic trade items found within these buildings, serve as an indication that Chaco was an advanced society with deep spiritual connections to the surrounding landscape.

Making this cultural fluorescence all the more remarkable is that it took place in the high-altitude semi-arid desert of the Colorado Plateau where even survival marks an accomplishment and that the long-term planning and organization it involved was carried out without a written language. This lack of a written record also contributes to a certain mystique surrounding Chaco - with evidence limited to objects and structures left behind, many tantalizingly significant questions about Chacoan society remain only partially answered despite decades of study.

Early Settlement

The first evidence of long-term human settlement in Chaco Canyon dates to the 3rd century CE with the construction of partially subterranean homes known as pithouses, structures which eventually were clustered together to form large villages. As inhabitants became increasingly integrated, single-story multi-room buildings began to appear in the 8th century CE among pithouse villages. Then, c. 850 CE, a remarkable change in Chacoan architecture began to take place which set it apart from that of any other Southwestern area. Whereas most contemporary buildings in the region contained less than ten rooms and were built out of wooden posts and adobe, Chacoans began to construct "great houses," colossal sandstone masonry structures which used thick walls to support multiple stories and hundreds of rooms. What it was that prompted such a dramatic and labor-intensive shift remains unknown today.

Continue reading...

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Only one more episode of my extensive and exciting podcast series over the history of the Anasazi / Ancestral Puebloans called The Ancient Ones remains and it’ll be out in a few weeks. I started with the Ice Age and I’ll end it with the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and the Spanish Reconquista that followed. So now’s the time to catch up and enjoy the sound of my soothing voice as I take you through the last 40,000 years or so of hunting, building, fighting, & flourishing that defined the American Southwest.

Pictured here are the remains of Spanish Catholic missions and churches, destroyed during the revolt, and the smoky kivas the revolt was planned in. All pictures by me, of course.

Stay tuned for more adventure!

#my podcast#the American Southwest#podcast#adventure#desert#southwest#arizona#utah#my photo#kiva#native americans#anasazi#history#ancestral puebloans#archaeology#anthropology

193 notes

·

View notes

Note

wait i’d love to hear yr thoughts about tony hillerman bc i grew up in new mexico (and still live here lol) & always thought he was just like normal pulp mystery

--

Normal pulp mystery with ten thousand digressions to talk about clouds and rocks. Hahaha.

IDK, do we use "pulp" like this now? (Genuine question.) His mystery style was fairly standard for the cozy end of mystery publishing if we mean not hardboiled, not police procedural, etc. rather than the cozy mysteries that are actually cozy with their cat-themed bookstores and such.

When I was a kid, my mother was obsessed with one day moving to Santa Fe, so for holidays, instead of seeing family, we'd go there. She had another phase where she was convinced she'd move to Orcas Island one day where, again, we spent holidays up around Seattle repeatedly. In both cases, there were things that happened to be culturally big at the time and easy to find that were also connected to local indigenous stuff.

What makes Hillerman interesting is that, despite being a white guy, he focused a lot on the Navajo reservation. It probably doesn't seem like much of anything if you're from that part of the world, and there are certainly some inaccuracies in the books that he himself would talk about in subsequent forwards, but they were a highly accessible introduction for someone who'd otherwise have had no reason to know about anything like that. I don't think that's so true now with more media on the scene, but this was the 90s at the height of his popularity (and of the series actually being good).

The thing is, they are normal mysteries. That's what made them work: people who didn't have a reason to care about the setting or particular political struggles bought them because they bought mystery novels in general. And then there was some other stuff in there too, but mostly, they're just fun genre fiction. One thing they did that I can't recall any other 90s media with a thousandth the reach doing was depict Indigenous characters who don't know that much about other indigenous cultures. There are a couple of books where the Navajo leads have to deal with Hopi stuff, and it's very clear these are different people with different communities. That sounds so incredibly small and obvious, but these books were sold in airport bookstores all over the country to an audience that knew literally nothing.

As for the books themselves, I like all the contemplative noodling about the landscape and the sense of place. That's something I often like in a mystery novel, especially one set somewhere I don't live.

The characters are compelling aside from their romances, which are horrendous. (Leaphorn has a wife who is a nonentity until she dies between books of something stupid, and then she comes up endlessly as the love of his life. Chee is a moron who makes bad choices and forces us to hear about them at great length.)

There's a bunch of archaeology stuff in some of the books, and I was a kid obsessed with archaeology. Honestly, our understanding of, e.g., Ancestral Puebloans is way different than it was in the 70s when some of these books came out, but it was still interesting stuff.

The adaptations now... Robert Redford bought the rights an eon ago and has been trying to make fetch happen ever since. One of the attempts was a set of three tv movies for PBS's Mystery! They hired Chris Eyre and unfridged Leaphorn's wife. There's a lot more humor relative to Hillerman's often rather gloomy style. And I am weak to buddy cops, to age gap with obnoxiously over-enthusiastic younger parties, and to OT3s.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feeding Alligators 35 - The Devil Wears Douchebag

Y'all meet a theater kid loser.

On AO3.

The Halsin guy is, once again, y’all’s best bet—no, Lae’zel, we don’t even know where the creche is and we do know where the goblins are and I promise if our dumb, istik brains get this wrong, we go there next.

Thank fuck for Gale and his teleports.

And your suspicions the night before were, in fact, entirely correct. Blood potion and dirt potion taste fucking horrific together. You futilely scrape your tongue with your nails in between gargling with tea (despite Gale’s wincing and “that was a perfectly good brew”). You’re so desperate, in fact, you try to gargle with wine.

Astarion laughs so hard when you choke that he almost rips open the seat of his pants as he keels over in hysterics.

Bastard.

But you can talk, your head feels calm and clear, and you’re not face-planting dead in the dirt.

“We cannot leave that devil to terrorize innocent people,” Wyll says as you swig the alcohol taste out with more tea (actually drinking it, this time, Gale).

He did agree to join y’all to get help taking that thing down. The brainworms fucked him up along with the others; man is down to a couple of spells a day. And the devil’s last known location was sort of in the vicinity of where y’all need to go anyway.

A demon hunt it is.

***

Y’all step through the swirling, swooshing purple portal into sunshine. Astarion isn’t the only one to sigh and turn their face up to bask in the warm, clean light. To a one, y’all’re coated in swamp muck and hag goo. There’s nobody on the road when y’all emerge, but you suspect anybody coming across you would give you a real, real wide berth.

The teleporter spits y’all out near the grove again. It’ll be several days’ walk to the goblin camp. But at least the crew knows this area well enough to find all the streams to camp next to.

Wyll chomps at the bit, though. His hero instincts can’t let y’all rest and clean up. So loathe as y’all are, y’all agree to set off now and make camp and wash your damn clothes later.

You ain’t that far from the grove when you notice the handholds carved into a cliff on your left. You saw similar marks when you went to visit a national park a few years back. Ancestral Puebloans used them to get up to their cliff cities down in New Mexico. You look up, and think you see the top of a structure up there. And more importantly, some kinda chest on that structure up there.

“I’ll be right back,” you say and unsling your pack. “Might be something useful.”

Lae’zel eyes the cliff and nods approvingly. Probably because this is exercise and while she left off going into the hag fight, she’ll be right back on your ass tonight, you reckon (your entire body is sore, but your pack seems a touch lighter than usual).

“I’ll go with you,” Wyll says. “We can scout the area from up there. Make sure there aren’t any goblin patrols.”

And then Astarion surprises all y’all. “I suppose I’ll go, too.” Catches all of you staring and rolls his eyes. “If someone died up there they might still have valuables.”

Of course. Mr. Sticky Fingers.

“Dibs on jewelry,” you say, because you haven’t forgotten that conversation and you can’t afford to back down on it.

He tilts his head, all amused, and Lae’zel makes a sort of low hiss in the back of her throat. Surprisingly, Shadowheart near mimics the sound. Then the two realize they agree on something and both appear pretty grossed out by the prospect.

The cliff ain’t one long wall, but a jumble of several shorter ones. Your boots are thin and flexible enough, and the angle just shallow enough you can scrabble up. Slower than both the boys—holy fuck, Astarion is fast at that but he frowns at his hands when you crawl up to join him on the first ledge.

Wyll, the gentleman, lets you go first in case you need a boost, but also scurries up beside you in case you need a hand at the top—which you do thanks to the whole “upper body strength deficiency” thing.

There is a structure at the top, alright. Real dilapidated, all wooden poles leaning haphazardly together. But there’s also a chest up there. Astarion volunteers himself. Shimmies right up, swipes the thing, and more slides than climbs down, the wood groaning and swaying alarmingly.

There’s no bodies, though. Just a moldy sack of some kind, and a spectacular view of the smashed open butthole ship.

“Damn,” you say, looking out. The debris field is huge, but the main shell of it seems to have landed close together. More like it dropped right outta the sky and cracked like an egg, less like an airplane shredding itself to pieces as it plowed across the landscape.

You wonder how the damn thing flew at all. No wings or rotors; probably wasn’t as fast as an actual airplane, since you doubt it had to generate lift like one. That lack of speed (and Not-Sasha) are probably what saved you from being roadkill.

“Quite the view, isn’t it?” Astarion says.

You hum. “I wonder if anybody else survived? Maybe fell out earlier, got saved by that dream douche.”

There’s a pause as you both wonder if that word translated correctly. Then Astarion moves past it. “If they did, they’re probably dead in a ditch somewhere by now.”

You give him a look.

“I’m just saying, we’ve been incredibly lucky. The wilderness doesn’t lack for monsters and bandits and cutthroats. Any one of us could have died at least twice by now had we found ourselves alone.”

“True,” Wyll comes in. He surveys the destruction below, and gives a slow shake of his head. “It almost makes you wonder if something else has a hand in all this.”

Astarion’s scoff is harsher than usual, his voice laced with heavy sarcasm. “You think gods saved us for some ‘higher purpose?’”

You could catch those air quotes blindfolded. You ain’t sure if he’s mocking the higher purpose, or gods in general (you try to hide the smile at either prospect). It is interesting, though, since gods are actually a physical thing, here.

“I’ve not seen the handiwork of many gods,” Wyll says. “But I have seen the influence of other things.”

“Ah! A well-traveled group, then!”

Y’all whirl, both men going for their blades.

Another guy stands behind y’all, dressed like a real fancy man, all ruffles and buttons and embroidery. You heard nothing from the other below to indicate y’all had company, and the man’s hands—held out as he dips into a theatric bow—are clean, his fingers well-manicured.

Fancy little fuck did not climb up here.

“Who’re you?” you say, dropping your customary swearing because this guy seems to have dropped clean out of the sky.

His eyes shift to you—

Oh. Fuck.

Those ain’t human eyes. That’s not a man. He’s man-shaped, but there’s something about the air around him, something that suggests an ill-fitted suit, like the atmosphere strains against the seams where he stands.

What the actual fuck is that thing?

“Such ferocity from one so defenseless,” he says, his voice pitched so low it goes gravelly.

Your lips hurt. They’re pulled back over your teeth in an animal snarl, you realize. Every hair on your body stands on end. Something about that thing ain’t right, ain’t natural, shouldn’t fucking be here.

“Who are you?” Wyll says as your monkey brain scrambles for human words.

The thing ignores him. Scopes the area with a disdainful air. “My, my, what manner of place is this? A path to redemption? Or a road to damnation? Hard to say, for your journey is just beginning.”

You immediately want to smash his teeth out. Not just because of the gibbering alarm shrieking in your skull; his entire vibe oozes pretension.

Which gets worse when he again, theatrically—still pretending y’all ain’t standing there, waiting for an answer—taps his lips with one finger. “What would suit the occasion? The words to a lullaby, perhaps?”

And then he launches into some goddamn poem. You don’t pay much attention—something about a cat. The talking pisses you off. Bitch drops out of nowhere and fucking monologues at you and you want to crawl out of your own skin. He rambles on and on until, finally, says his name: Raphael.

There’s no magic translation of his name. It really is “Raphael.”

Which is a Hebrew name.

It is an angel’s name.

You don’t think this thing is an angel what the fuck.

Your companions both look to you, for some reason, and when you still don’t speak (please be wrong, please be wrong, please your mother cannot be right about this), Wyll ventures a, “Are you the cat or the mouse?”

And hoo boy. Does this (demon demon demon) man look fucking ecstatic with somebody playing along.

Your mother and the others loved talked about the devil. Loved. Demons and evil and witches and sin. Couldn’t somebody spit out more than three sentences without bringing one of them into it, up to and including passing the salt at breakfast.

You left all that behind. Slowly, deliberately. Like pealing leeches—fat and gorged and pulsing with your own, stolen blood—from your body. Each belief, each phrase, each word carefully (or extremely rushed in a fit of anger) pulled out, mouths chomping and bloodied. Each one dropped into the dirt and left behind to rot.

Now you’re here, with wizards and vampires and a literal fucking soul trying to fly off into space, and you look at this monologuing motherfucker, and something long dead stirs within you.

(demon demon demon)

You been palling around with killers and monsters. But now, in front of this creature, you feel the first brush of evil.

Raphael lifts his fingers. He’s been talking; you were too busy keeping your limbs still, knees locked, keeping yourself upright. Now he snaps, and the world shifts—

You’re in some ugly fucking dining room. Everything in red and gold and black, like a migraine made visual. Fireplaces big enough to stuff a fucking buffalo into. Paintings of demons (yep, those’re demons) on the walls. It’s all opulent and gauche in a nauseating way.

Voices startle behind you. The rest of the crew, clutching their weapons, eyes wide, teeth bared in Lae’zel’s case and huh, she’s an alien entity to these people and the two of you seem to have the same reaction to that thing.

Beyond them, you spot another painting. A red demon, big, bat wings spread wide, dressed in frilly, foppish finery. Skull in one hand. Same, smug face as the creature standing in the room with you.

Motherfucker.

“What’s going on?” Gale says. “Who…?”

“Welcome, welcome to the House of Hope,” Raphael says. Gestures to the huge table piled three tiers high with food. It even smells good. You been living off stews, sausage, and cheese for a week. That pie looks so flaky and tender, your mouth actually waters. “Please, help yourselves. Enjoy supper. It might be your last.”

“Don’t touch the food,” you say. So many stories about abductions and food. Fairies, Greek gods, and that one Guillermo del Toro movie with the pale man.

This, unfortunately, draws the attention of the sonuvabitch back to you. Jesus lord, his face is so sleazy. He cocks his head. Studies you.

“Yes, you’re an interesting case, aren’t you?” he says. His voice dips even lower, going ragged in his throat like he’s trying too hard. “Not from around here. You notice it, don’t you? You and the gith, both.”

“Notice what?” Wyll says.

“That creature cloaks its appearance,” Lae’zel says. Much better wording than your own, mental his skin is fucking fake!

“Indeed,” Raphael says. He tosses an arm into the air as if to present a stage line. Only hot wind buffets out from him, stinking of ozone and sulfur. And when you blink through watering eyes, there stands the red motherfucking demon from the painting.

Wyll tenses beside you. Astarion has gone utterly still, not even pretending to breathe.

Raphael smirks. Says, “What’s better than the devil you don’t know? The one that you do.”

“No,” you say.

You don’t mean to say it. You have every intention of staying still and quiet, like Astarion. Of fading into the background and hoping the bad thing doesn’t notice you until y’all can get the fuck outta here.

But this is all too much, and you’re flat out panicking and (demon demon demon the devil will steal your soul). It just sort of slips outta you.

Raphael frowns, mildly. Cranks up the sleaze. “I’m afraid I haven’t even—”

“No thank you we’d like to go now—” You clap both hands over your mouth. Resist the urge to walk over to the nearest wall and lobotomize yourself through sheer blunt force trauma.

At least a few self-preservation instincts manage to reach in and make sure it comes out sorta polite?

The next frown is not mild. “Ill manners make an ill guest. On this plane and in all others.”

You’re done talking. You’re done moving. You can feel the sweat beading in your armpits and along the edge of your scalp.

Raphael’s creepy demon eyes hold your gaze a moment longer. When you sensibly keep your lips shut, he resumes his monologue. You all but sag against Astarion when the demon shifts to address the others.

Something something brainworms. Something something he’s your savior (you’ve had quite enough of those to last a lifetime). Something something grandiose pretension.

“I could fix it all like that.” Raphael snaps his fingers. Flames burst up from his hand.

Neat party trick, you think and absolutely do not say.

He wants y’all to ask for help. Says y’all won’t find any with Halsin or Lae’zel’s people. He says all that in the nastiest, most arrogant way possible, and your companions look at each other, unsure. One of them is gonna say something stupid, ask for more information, actually consider what this fuck is saying.

“I thank you for your hospitality,” you say. Your voice only shakes a little. You’re almost proud of that. “But I have to insist we leave.”

Maybe it’s the extra courtesy in your phrasing. Or maybe he’s too wrapped up in the sound of his own speech. He sweeps right into his next schtick of “blah blah denying reality, blah bah change your mind, you’re so weak, you’ll come crawling back, blah blah.”

Wyll is damn near trembling to one side. There’s a look in his eye part contained anger, part fear.

“You’ve been lucky so far,” Raphael wraps up. “And I’ll be there when that luck runs out.”

He snaps his fingers.

You’re once again on a cliff, under a blue sky smelling of pine and distant water and the slightest tinge of burning slugs and rubber.

None of the others gives you crap as your legs give out.

Previous - Index - Next Chapter

#feeding alligators fic#these two shitheads#bg3 fic#astarion fic#tavstarion#astarion x tav#isekai#plus size tav#demisexual tav#slow burn#like reallllllly slow#they're both dumb

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Seven Cities of Gold

I've always been a little fascinated in how myths affect myths and one great example of this is the Seven Cities of Gold. This, primarily, is considered one of the oldest European-American myths, one created by Spanish colonists and invaders.

The Seven Cities of Gold, or the Seven Cities of Cíbola, was a Spanish myth of indigenous cities built of or filled with gold, around the beginning of the sixteenth century. They are most closely associated with the 1540 entrada headed by Vasquez de Coronado into primarily modern day Arizona and New Mexico. The origin of this myth, however, is a bit confusing, for a couple reasons.

There are no Seven Cities of Gold

Which Seven Cities has never actually been solidified

This myth seems to predate European knowledge of the Ancestral Puebloan cities in New Mexico for which they are named (Cíbola being one of the first terms Europeans used to describe Zuni)

Which gets into the reason as to why such a myth exists. Fundamentally, (in my opinion) there are two factors that resulted in the creation of the myth of the Seven Cities of Gold: the economics of slavery and abolitionism, and the age old equivalent of the game Telephone.

The economics and history of slavery at this time, I think is fairly well understood, but I digress: Spain colonized Mexico and every other part of the Americas they could reach for imperial advantage. Spain needed money to fund its Inquisition (yes that one), and to rebuild after the Reconquista. As imperial powers do, they needed a source of income, preferably with unpaid labor. The Americas provided both of these, especially in Southern Mexico, where the Aztecs, already quite adept at mining and refining gold, had populous cities and traversable infrastructure. The Incas, like the Aztecs, also indicated to Spain that the Americas were filled with the riches they desired (people they could enslave, and precious metals - especially gold and silver).

Abolitionism on the other hand, especially in the early 1500s, is something I don't really hear so much about, even though it was a strong political force at the time. Granted, not abolitionism in the way we think of it today - let's not pretend that democracy was even on the horizon. But at the very least, Spain was at the forefront of a political movement away from the equivalent of chattel slavery - a shift the US would not catch onto for another three hundred years. The human rights violations of Spain's early conquistadors (and yes, the people of that time also thought of it that way) were abhorrent both politically and - worse for Spain - economically. Surprising to no one, someone willing to commit the worst acts imaginable on another human being is not all that willing to then go along with society's basic functions of decency. If you can name an early conquistador, I can name exactly how they fell from grace, were convicted, exiled, or yes - even murdered. It's all of them. So, Spain had a human rights movement, which manifested in several "protectionary" laws for the indigenous - especially the Laws of Burgos and the Ordinances of Discovery (I use quotations because, again, Europeans were still doggedly racist, and these laws reflected this). Some of these laws were so humanitarian in nature, Spanish colonists revolted in some areas because of how many rights were being granted to the indigenous (truly, please read about Pizarro's assassination, it's magnificent, and contextually relevant).

One actor in this movement, of course, was the first viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza. Mendoza, while politically very shrewd, was in favor of these humanitarian movements. He would not have agreed to breech the northern border of his colony - was was then Central/Northern Mexico - only to conquer, like those before him. That position of his changed only after a survivor of a once-thought-to-be-very-very-very-dead entrada from ten years prior wandered out of Northern Mexico and back into Spanish occupied lands - Cabeza de Vaca. De Vaca spoke of cities he had been told about that were encrusted with jewels. This, Mendoza would move for, so he sent a scouting party, the survivors of said party returned to say they had also been told stories of cities of gold. Somewhere along the way, this report was twisted to say that the scouting party had actually seen cities of gold - specifically the city Cíbola (Zuni). Gold moved Spanish action, this is a constant through history. So Mendoza began preparing the first entrada of his office - the entrada of Coronado. From there, it's history (Coronado was also a fail-son like every conquistador before and after him. Look it up, he's cringe.).

But, where the fuck did the myth of Seven Cities come from? The scouting party saw one (1), and it was from a distance. This is where we get into the equivalent of the game of Telephone, aka how information was disseminated for nearly humanity's entire existence until the Phoenicians.

Humans, oddly enough, have a penchant for the number 7. We just really like it, for whatever reason. Lots and lots of legends and myths involve the number 7, but the two specially that likely influenced the myth of the Seven Cities come from two backgrounds - the Seven Caves of Chicomoztoc, and the Seven Cities of Antillia. Fascinatingly, two completely separate myths that evolved entirely independently of each other. The Seven Caves is a Nahua (Aztec) myth, about the origin of the Nahua themselves. Like many other Central American and American Southwestern peoples, the Nahua origin myth tells of the people emerging from the underground, specially from seven caves in this instance. It's an absolutely beautiful reminder just how well humans are able to keep our history even without writing it down. Unfortunately, the Spanish heard this myth, and thought 'Oh, how great would it be if we could find these caves, and loot them.' After all, the great Aztec cities they'd looted so far yielded a lot of gold. So, already, Spanish colonizers were primed with the desire to search for yet-to-be-discovered hordes of gold.

The second myth is of European origin, before the Americas were ever sailed to. The myth of the "lost" island of Antillia, or the Seven Cities of Antillia, revolved around a phantom island, of all things. Phantom islands are islands that do not exist, but were created through mapping errors when maps were made by hand by some guy going "yeah that looks about right". Maps were collaborative, so if some guy put down on the portion of the sea that he'd mapped that there's an island there, the next person over would also put it down, because how is he to know that the first guy was wrong. Phantom islands were chronic in early seafaring, because people also have a penchant for, scientifically speaking, making shit up. (See early maps of the gulf of Mexico, it does wonders for imposter syndrome. They were legit just making shit up.) The phantom island of Antillia was an island once incorrectly drawn off the coast of the Iberian Peninsula, long before 1492, and was said to be the hiding place of several prominent members of the Catholic Church - with highly desirable land and lots and lots of money. It was this myth that already existed in the mind space of Spanish citizens, once again priming them for the rumors told of Cíbola.

There have of course been speculations of what the Seven Cities might actually be, or at the very least, the remaining six, but it remains a fact that there were no cities of gold. No matter how much National Treasure 2 wants us to think it's in some god forsaken place like South Dakota.

#yes i wrote this whole thing to shit on south dakota for a bit#but anyway#here's a bit of actually interesting american lore#mythology#nahua mythology#seven cities of gold#seven cities#antillia#phantom islands#history#anthropology#this was also a chance for me to shit on coronado specifically#all my homies hate coronado#what a fucking loser#coronado#the only conquistador more cringe than him is onate#i wish i could trace my fascination with this era of history to a specific point but really it's just the madness that comes from wikipedia#that is the gods honest truth#'is this about puaray' everything is about puaray#puaray is my roman empire leave me alone

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

History buffs and travel enthusiasts, this one's for you! Have you ever dreamt of walking through ancient cities or marvelling at age-old structures? Well, you don't have to embark on an Indiana Jones-style expedition to experience the thrill of archaeology. Here are 5 incredible archaeological sites that are surprisingly accessible: Pompeii, Italy: Travel back to 79 AD and explore the frozen-in-time Roman city of Pompeii. Witness the everyday lives of its inhabitants preserved by volcanic ash, from homes and shops to haunting body casts. Numerous tours are available, and Pompeii is easily reached by train or car from Naples or Rome. Acropolis, Athens, Greece: Ascend the sacred hill that housed the Parthenon, a temple dedicated to the goddess Athena. Explore the ruins of other significant structures like the Propylaea gateway and the Erechtheion temple. Athens is a well-connected city with a robust tourist infrastructure, making the Acropolis a breeze. Chichen Itza, Mexico: Immerse yourself in the Mayan civilization at Chichen Itza, a sprawling complex featuring the iconic pyramid-temple of Kukulkan (El Castillo). Explore other structures like the Temple of Warriors and the Ball Court, all remnants of a powerful Mayan city. Chichen Itza is close to popular tourist destinations in the Yucatan Peninsula, making it a convenient stop. Colosseum, Rome, Italy: Step into the gladiatorial arena of the Roman Empire at the Colosseum. This awe-inspiring amphitheatre is a testament to Roman engineering and entertainment. Guided tours provide a glimpse into the history of gladiatorial combats and public spectacles. The Colosseum is a must-see for any visitor with its central location in Rome. Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, USA: Journey back to the cliff dwellings of the Ancestral Puebloan people at Mesa Verde National Park. Explore cliff houses and villages built into the canyon walls, offering a sense of the ingenuity and lifestyle of this ancient civilization. The park offers tours and ranger-led programs and is easily accessible by car.

#travel#travel destinations#europe#italy#greece#mexico#archeology#history#history travel#usa#travel inspiration

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colorado was admitted as the 38th U.S. state on August 1, 1876.

Colorado Day

Colorado Day is celebrated annually on August 1. The holiday commemorates the admittance of Colorado as a state of the Union on August 1, 1876, thanks to an Act of Congress signed by President Ulysses S. Grant. Before the Spanish started settling in Colorado as far back as 1598, Native American tribes had inhabited the area for about 14,000 years. In March 1907, the state legislature officially passed a law designating August 1 as Colorado Day; thus, the holiday started holding on August 1, 1907.

History of Colorado Day

About 14,000 years ago, several Native American tribes, including the Ancestral Puebloans, Apache, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Shoshone, and Ute nations, inhabited Colorado. The first European contact was by the Spanish conquistadors, one of whom — Juan de Onate — founded the Spanish province of ‘Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico’ on July 11, 1598. Eventually, Colorado became a part of this province, and the regular trade between the Spaniards and Native Americans who lived there became known as ‘Comercio Comanchero,’ meaning ‘Comanche Trade.’

In 1803, the United States made a territorial claim to the eastern part of the Rocky Mountains, which the Spanish, who claimed sovereignty over the territory, contested. In 1846, the U.S. went to war with Mexico, winning and claiming the Southern Rocky Mountains for American settlement. However, it wasn’t until a few years later that settlement began in earnest due to the ‘Pikes Peak Gold Rush.’ On June 22, 1850, a man called Lewis Ralston discovered gold in a stream flowing into Clear Creek; he immediately named the stream ‘Ralston’s Creek.’ In 1857, gold seekers began flooding the territory to search for gold — this led to the beginning of the “Pikes Peak Gold Rush.” Three years later, an estimated 100,000 people had come in search of gold, which caused a population boom. However, they settled for silver, hard rock gold, and other minerals when the gold eventually got exhausted.

On February 28, 1861, Colorado became a U.S. territory by an Act of Congress signed by President James Buchanan — this happened during the infamous secession of the Southern States that led to the American Civil War. On August 1, 1876, President Grant signed a proclamation admitting Colorado to the Union as the 38th State, 28 days after the Centennial Celebration of the United States, earning it the moniker “Centennial State.” ‘Colorado Day’ was first celebrated in 1907.

Colorado Day timeline

1598 Entry of the Spanish

The Spanish conquistadors begin the first European settlement in Colorado.

1850 Ralston Discovers Gold

Lewis Ralston discovers gold in Clear Creek.

1858 Gold Rush Begins

The ‘Pike’s Peak Gold Rush’ begins.

1861 Colorado Becomes a U.S. Territory

Colorado is a U.S. territory after President James Buchanan signs an Act of Congress.

1876 Colorado Becomes a State

Colorado gets admitted as the 38th State of the Union by a signed proclamation of President Ulysses S. Grant.

Colorado Day FAQs

Who’s the current leader of Colorado's government?

The current governor of Colorado is Jared Polis, who has been in office since 2019.

What is the population of Colorado?

Colorado is home to approximately 5.8 million people.

What is Colorado known for?

Colorado is well known for its beautiful landscapes, wildlife, and various outdoor activities the state offers, such as mountain biking, horse riding, and skiing.

Colorado Day Activities

Say “Happy Colorado Day!”

Study the U.S map

Learn more about Colorado

Celebrate by wishing all Coloradans a ‘Happy Colorado Day!’ Send a goodwill message to all Coloradans you know or post a kind message online.

Study the map of the United States and try to locate Colorado. If you don’t have a physical map, tons are available online.

There’s so much rich and fascinating information about the state of Colorado. Conduct some research and even plan a future visit. Begin from our “facts” section and explore further!

5 Random Facts About Colorado

Colorado was ahead on women’s rights

Four states meet in Colorado

Colorado holds a world record

Another world record!

Home to America’s highest suspension bridge

On November 7, 1893, women won the right to vote in Colorado, becoming the first Union state to achieve this.

Colorado borders Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, making it possible to be in all four states simultaneously!

At 1,002 feet deep, the Mother Spring aquifer is the world’s deepest hot spring.

Spanning several 100 square miles, the Grand Mesa in Colorado is the world’s largest flattop mountain.

At 1,053 feet, the Royal Gorge Bridge is the country’s highest suspension bridge.

Why We Love Colorado Day

Colorado Day commemorates the state’s history

Colorado Day is for celebration

Promotion of tourism

Colorado Day commemorates and reflects on the state’s history. It’s also an opportunity to educate those who know little about Colorado’s origins.

This day also allows Coloradans to celebrate their state — whether native Coloradans or foreign residents. Embracing our roots is vital!

State days promote tourism, which boosts the local economy. Publicizing the beautiful attractions and natural sights in Colorado encourages more people to visit.

Source

#Douglas Pass#Colorado National Monument#Ridgway#Denver#Old Colorado City#Colorado Springs#San Juan National Forest#Wolf Creek Valley#Wilkerson Pass#Square Tower House#Mesa Verde National Park#Kaan Paachihpi#Durango#cityscape#landscape#summer 2022#original photography#tourist attraction#landmark#Colorado#38th US State#1 August 1876#anniversary#US history#Colorado Day#ColoradoDay#travel#USA#architecture#vacation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

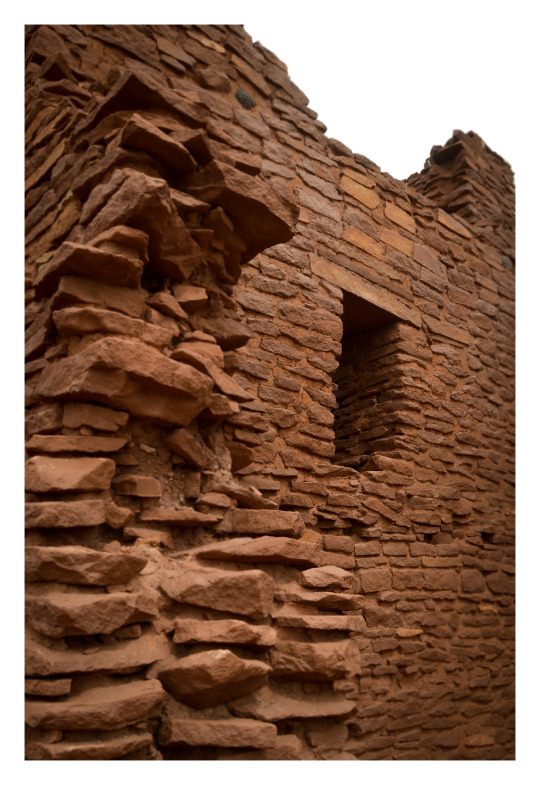

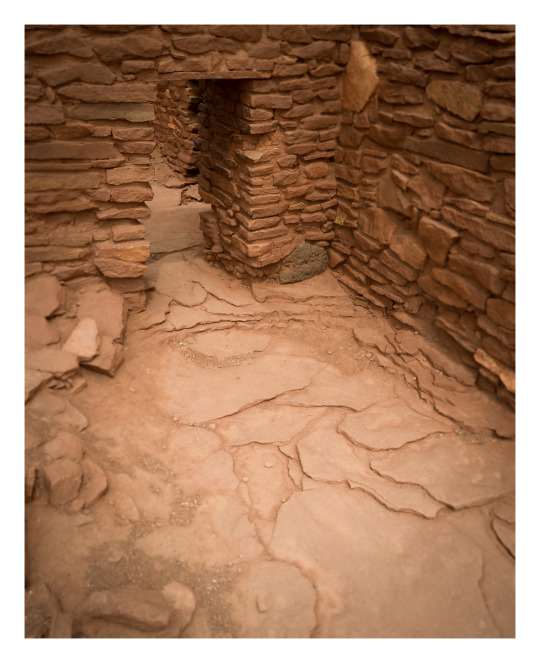

Untitled.

#photographers on tumblr#masonry wall#Wupatki National Monument#Ancestral Puebloan People#Coconino County#Arizona

63 notes

·

View notes

Video

Guest Viewings of Chaco Culture National Historical Park by Mark Stevens Via Flickr: A setting looking to the east while taking in view across the Chaco Culture National Historical Park landscape present to my front. In composing this image, I took advantage of some high ground. I was located on an angled my Nikon SLR camera, so that I could create more of a sweeping view, leading off into the horizon. I wanted to keep a balance between the blue skies and clouds above with the earth-tones in the lower portion of the image. I felt there was a color contrast that seemed to complement the entirety of the image.

#Ancestral Puebloans#Azimuth 92#Blue Skies#Blue Skies with Clouds#Chaco Culture National Historical Park#Chacoan Culture#Cliff#Cliff Face#Cliff Wall#Cliffs#Colorado Plateau#Day 2#Desert Landscape#Desert Mountain Landscape#Desert Plant Life#DxO PhotoLab 7 Edited#Intermountain West#Landscape#Landscape - Scenery#Looking East#Mesa#Nature#New Mexico and Mesa Verde National Park#Nikon D850#No People#Outside#Partly Cloudy#Partly Sunny#Portfolio#Pre-Columbian Cultural

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Do you have any book recs for your period in Southwestern history/archaeology? Literally anything that you find neat.

Sincerely, a Southwesterner who does archaeology elsewhere

I've been thinking about this! The thing is, most of the ones I know are aimed at academics.

Living and Leaving: A Social History of Regional Depopulation in Thirteenth-Century Mesa Verde by Donna Glowacki is the single best book about the period when people left the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde en masse in the late 1200s-early 1300s to migrate south along the Rio Grande, and the way it completely changed up the social organization of the whole region. (The aftermath of this is the time period I study the most, so I refer back to this one a lot.)

The Continuous Path: Pueblo Movement and the Archaeology of Becoming edited by Sam Duwe and Robert Preucel is a really good collection of articles centering archaeology interpretation through Puebloan philosophy on migration, movement, and relation to landscapes.

As an archaeologist, if you're into more academic stuff, Ancestral Hopi Migrations by Patrick Lyons and In the Aftermath of Migration: Renegotiating Ancient Identity in Southeastern Arizona by Anna Neuzil are other seminal monographs I reference constantly. They're really foundational to the study of Pueblo IV migration and reorganization in the 1300s and 1400s.

The place I earnestly direct people to is Sapiens magazine, some of the best anthropology writing for popular audiences that doesn't require you to have access to academic libraries lol. Here are a discussion of "abandonment" and moving from places like Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde in the archaeological past from a Native perspective, the timber used to build Chaco Canyon great houses, the timber used to build the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings, a Hopi archaeologist's opinions on why Ancient Apocalypse is disrespectful to Hopi and other Native history (and his perspective on Hopi relationship to history and place), and just for fun, a photo essay on Pueblo ladders,

And here's some reporting on the chocolate mugs from Chaco Canyon because they're amazing but all the really good writing about them is SO academic. (here's the initial article, which is dry but I love, and here's the book she expanded it into.) (Writing about this cool stuff in ways people actually want to read is a real unfilled niche!!

Some other books I like that are kind of outside my particular temporal scope but I find fascinating anyway:

Wisdom Sits in Places by Keith Basso is one of the most accessible, non-academic ones. It's an Apache perspective on landscape and history and Apache language and history through landscape. Some history, a lot of philosophy.

Maso Bwikam / Yaqui Deer Songs by Larry Evers and Felipe Molina is part poetry collection and part long explanations of the Yaqui deer dance history and tradition that was really fascinating.

Also, I'm curious about what archaeological work you do!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anasazi Indians: The Ancestral Puebloans were an ancient Native American culture centered in present-day Four corners area of the United States, comprising Southern Utah, Northeastern Arizona, Northern New Mexico, and South Western Colorado.

They lived in a range of structures, including pit houses, pueblos, and cliff dwellings designed so that they could lift entry ladders during enemy attacks.

The people and their archaeological culture were historically called Anasazi from Navajo term Anaasazi, meaning "Ancient Ones"

Between 300B.C. and 100A.D., there were four distinct Indian cultures settled in SouthWest, Anasazi, Mogollon, Hohokam, and Sinagua. The fifth culture, the Fremont Indians settled primarily in Utah in 400A.D.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Homolovi

Homolovi or Homolovi State Park (formerly: Homolovi Ruins State Park) is a cluster of archaeological sites that contains the ruins of eight pre-Columbian Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) and Hopi pueblos in addition to some 300 other remains and petroglyphs. Homolovi lies within sight of the Little Colorado River in a floodplain, 2 km (4 miles) northeast of Winslow, Arizona in the United States. Archaeologists believe that Ancestral Puebloan peoples and the ancestors of the Hopi tribe once occupied these settlements, which spread out along a 32 km (19 miles) corridor on the Little Colorado River, at different intervals of time from c. 1250-1425 CE. Two pueblos - Homolovi I and Homolovi II - each contained more than 1,000 rooms in ancient times, and 40 ceremonial kivas are scattered throughout the park. The Homolovi ruins are unique in the ancient Southwest as they have helped archaeologists better understand the cultural transitions and social changes that occurred in the region during the 13th through 14th centuries CE. Four of the sites at Homolovi are listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, and the park is currently managed by the Arizona State Park system.

Geography & Prehistory

Homolovi or Homol'ovi is Hopi for “place of the little hills,” and Arizona's Hopi Reservation and Hopi Mesas are located only 84 km (52 miles) north of Homolovi. Lying in extreme close proximity to the Little Colorado River (Hopi: Paayu), Homolovi is situated in the Great Basin Area Desert Grasslands and is 130 km (80 miles) southeast of Flagstaff, Arizona, 117 km (73 miles) from Wupatki Pueblo, and 217 km (135 miles) west of Gallup, New Mexico. Homolovi covers a total area of 1,800 ha (4,500 acres) and sits at a high desert altitude of 1494 m (4,900 ft). Homolovi only receives about 178 mm (7 in) of precipitation annually.

Scientific and archaeological research has shown that nomadic, prehistoric peoples occupied the area that now comprises Homolovi intermittently from c. 4000 BCE- 400 CE. The Little Colorado River made the area somewhat attractive to an array of fauna: cottontail rabbits, jackrabbits, beavers, prairie dogs, porcupines, waterfowl, fish, elk, deer, and antelope come to the river seasonally. Ancient prehistoric peoples and tribes came occasionally to the region while hunting and migrating seasonally, but they did not construct settlements within the region until c. 500-600 CE. The reasons for this are likely due to the area's very dry climate and lack of wood and storable food resources. When possible and climatic conditions were favorable, early sedentary people hunted and gathered like their prehistoric forebears, but they also began farming, growing corn, beans, squash, and other small crops. It is also known that they grew cotton for textile production. Yucca and rice grass have grown in the area for several millennia, and indigenous people utilized rice grass as a staple food when the maize crop failed.

There were two periods of inhabitation of Homolovi prior to the construction of the pueblos at Homolovi in the 13th and 14th centuries CE: an Early Period from c. 600-900 CE and Middle Period from 1000-1225 CE. When favorable climatic conditions existed in the 11th and 12th centuries CE, indigenous peoples built small pit houses as opposed to large-scale constructions made of adobe. These earlier occupations of the area around Homolovi appear short-lived and sporadic, lasting around a decade or two. This pattern of periodic settlement and abandonment is likely due to changing local environmental conditions and the Little Colorado River. Depending on the year, the river could be bone-dry due to lack of rain or prone to flooding due to heavy snowfalls near the river's headwaters. It is known that the Little Colorado River was flooded regularly in the early 1200s CE and that the decades leading up to the 13th century CE were wet.

Continue reading...

21 notes

·

View notes